Friday, July 28, 2006

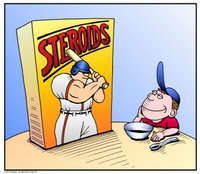

Out-Landis Drug testing?

I think many of us were surprised and saddened to hear about the results of Floyd Landis’s drug test after his stunning Tour de France victory. I know I was. But I was also intrigued that he vehemently denied the results and demanded another test.

This got me curious, how do they test for doping in sports? And where is the gray area?

It seems there is no direct test for steroids; rather, tests are done to check for abnormally high levels of testosterone in relation to something known as epitestosterone. In the case of Landis, he did not show high testosterone levels, he simply showed a high ratio. It seems the average person has a 1:1 or maybe 2:1 ratio and Landis had more like a 9 or 10:1 ratio. However, epitestosterone has no adverse effects, and according to www.howstuffworks.com (http://entertainment.howstuffworks.com/athletic-drug-test6.htm) it would be ok for an athlete to inject him/herself with epitestosterone to lower the ratio and mask high levels of testosterone. Wouldn’t Landis have tried that if he had used steroids and believed he had something to hide?

An article appearing on slate (http://www.slate.com/id/2146630/?nav=tap3) by Brian Alexander notes that Landis could likely be innocent of doping, as the test does not actually detect steroids, but instead looks at the ratio between the proteins described above. If you ask me, Landis’s results merely look ‘suspicious’ and are nowhere near actual proof of doping.

Further, the slate piece asks, ‘if a test won’t stop doping, what will?’

Alexander points to the Italian model of anti-doping where athletes face criminal prosecution such as fines or prison time if found guilty. Would that ever happen in this country?

I think before we can consider tougher anti-doping laws we need to find a test for doping that will hold up in court.

Wednesday, July 26, 2006

The Science of Addiction

I brought the article up over dinner the other night with a friend who is about to begin work on a Ph.D. in clinical psych. I thought the phenomenon made a strong case for the biology of addiction versus the psychology of it.

And my wise friend (I miss you already Jamie!) used a good analogy of the blind men holding onto the elephant; each one holds a leg, or a tail or the trunk and they are so sure not only that it’s an elephant but that they are the only person holding onto it. At least I think that’s how the analogy goes. In any case, his point was just that you can have half a dozen people study addiction, and each one makes a strong case for the biology of it, or the psychology of it, or the genetic dependence, and no one is wrong.

In my quest to find some insight on the subject I came upon this article.

http://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/pto-19940901-000020.html

The article references the ‘disease theory’ of addiction, which prevails at least among us ‘laypeople’ in this country, the theory being that alcoholism is a disease, and either you have it or you don’t; if you have it you can’t change it and if you don’t have it you need not concern yourself. Although the theory works well for us on a daily basis; alcoholics absolve themselves of responsibility, non-alcoholics sleep well believing there is no risk, academics are claiming it isn’t quite so clear cut. Apparently the mechanism to become addicted may be universal and lie within all.

"The most likely truth about addiction is that it's not a single, basic mechanism, but several problems we label 'addiction,'" says Michael F. Cataldo, Ph.D., chief of behavioral psychology at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutes. "No one thing explains addiction," echoes Miller. "There are things about individuals, about the environment in which they live, and about the substances involved that must be factored in." Experts today prefer the term "addictive behaviors," rather than addiction, to underscore their belief that while everyone has the capacity for addiction, it's what people do that should drive treatment.”

I wonder what it would take to change prevailing ‘disease’ theory?

Tuesday, July 25, 2006

My genetic testing results-

But the process got me wondering just how common it is for women (or men) to undergo genetic screening to see if they are carriers for disease. According to a website from Montefiore medical Center (http://www.montefiore.org/services/coe/womenshealth/prenataltesting/):

“Genetic testing is an increasingly important aspect of prenatal care. Just consider the directive released in 2003 by the American College of OBGYN and the American College of Medical Genetics, under the offices of the National Institute of Health. It mandated that every woman be informed that parents can now be tested for the cystic fibrosis gene.”

Those are strong words for NIH. If each woman is informed that parents can be tested for the cystic fibrosis gene, where do we draw the line? Do we just add to that list as we isolate genes? What about significantly less threatening genetic diseases, do we mandate that women know about those? Is it irresponsible to not inform would-be parents of the possibility that their child will have Aspbergers (for example)?

But what do we do with this information?

There is a difference between knowing that you are a carrier for a disease and actually testing an unborn child. If you test an unborn child you prepare yourself for certain possibilities, but simply testing to see if you’re a carrier doesn’t require any further action, right? And if it doesn’t, should we be mandating it?

Thursday, July 20, 2006

Why its called 'The Iron Ring'

I’ve been writing this blog for about a month now, and so I’ve decided to pause today to explain why it’s called ‘The Iron Ring’.

‘The iron ring’ refers to an old Canadian engineering tradition, the details of which are available on the following website (http://www.ironring.ca/), including how Rudyard Kipling is involved, and the details surrounding something known as ‘The Corporation of the Seven Wardens’. I’ll spare those details here.

In Canada, when an engineering student graduates from University (they only call it ‘University’ there, never ‘College’) they receive an iron pinky ring in a very secret ceremony. As I am not Canadian, and therefore not privy to this ceremony, I can only recount what I have been told. In essence, a person who has worked as an engineer for at least ten years, or a professor, bestows the iron ring upon the graduating student along with the ‘obligation’ to their profession. To quote said website:

“The ring symbolizes the pride which engineers have in their profession, while simultaneously reminding them of their humility. The ring serves as a reminder to the engineer and others of the engineer's obligation to live by a high standard of professional conduct.”

Or as my brother says, it lets everyone know exactly who to beat the crap out of.

In any case, the ring is made of iron to remind engineers that when they design structures like bridges, they must do it correctly or else people could die. It’s an interesting perspective, as most people would not consider engineering a ‘life or death’ profession and most engineers are not the ‘live on the edge’ types.

In any case, I was discussing famous engineering mistakes with my only Canadian-engineer friend a few weeks ago and I mentioned that the tradition of the iron ring seems a bit outdated for the more modern definition of engineer, as I am a ‘bioengineer’ and I don’t build bridges or design cars. And he made the interesting point that bioengineers have responsibilities to society too; some of us design prosthetic devices, or study medical imaging, or develop devices that aid researchers in modeling disease. We have our own obligation to the iron ring.

And so, in honor of that obligation I have started this blog. I intend to explore issues of scientific and engineering responsibility, and give myself an outlet to examine my role in the scientific endeavor. Let me know what you think!

Tuesday, July 18, 2006

(Wo)men in Science

Appearing this week in Nature is a commentary entitled ‘Does Gender matter?’ written by a Ph.D researcher at Stanford named Ben Barres. The catch is, Ben used to be Barbara.

In the Science Times, Cornelia Dean asks of him:

(http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/18/science/18conv.html?_r=1&oref=slogin)

“Q. What about the idea that men and women differ in ways that give men an advantage in science?

A. People are still arguing over whether there are cognitive differences between men and women. If they exist, it’s not clear they are innate, and if they are innate, it’s not clear they are relevant. They are subtle, and they may even benefit women.

But when you tell people about the studies documenting bias, if they are prejudiced, they just discount the evidence.

Q. How does this bias manifest itself?

A. It is very much harder for women to be successful, to get jobs, to get grants, especially big grants. And then, and this is a huge part of the problem, they don’t get the resources they need to be successful. Right now, what’s fundamentally missing and absolutely vital is that women get better child care support. This is such an obvious no-brainer. If you just do this with a small amount of resources, you could explode the number of women scientists.”

I think childcare is a good place to start for looking at inequalities in a wide range of careers, but particularly in science and particularly in academia. Note this bit of news out of Berkeley http://www.berkeley.edu/news/berkeleyan/2003/04/30_facfam.shtml. Although the research is three years old now, pie charts indicate that 75% of female assistant professors have no children in their household, as opposed to only 58% of male assistant professors. The tenure system, as pointed out in this piece, is a prime example of how academia is structured against not only women, but also young families. The time taken to obtain tenure is lengthy and often corresponds to childbearing years.

Sadly, I think it will take two major steps to remedy this; one, the institution of new family-friendly policies and two, the end of stigmatizing those faculty who take advantage of them. There is a big difference between the rules on the book and the ones in practice.

Saturday, July 15, 2006

Writing the gospel-

The letter is written specifically in regard to statements made by David A. Prentice Ph.D, a man who advises at least one senator and several other opponents of embryonic stem cell research. In Prentice’s words “Adult stem cells have now helped patients with at least 65 different human diseases. It’s real help for real patients”. However, the authors of this editorial do not agree with these statistics, and they proceeded to pick apart each of his references one by one and demonstrate that “A review of those references reveals that Prentice not only misinterprets existing adult stem cell treatments but also frequently distorts the nature and content of the references he cites”.

In addition to having a Ph.D, Prentice is a Professor of Life Sciences at Indiana State University and Adjunct Professor of Medical and Molecular Genetics at Indiana University School of Medicine. And, in addition to advising a host of policymakers on issues of science he is a founding member of Do No Harm: The Coalition of Americans for Research Ethics (http://www.stemcellresearch.org/). Finally, if there was still any lingering question as to whether Dr. Prentice’s beliefs were driven by religion, he recently spoke at the 2nd International Christian Medical Conference on alternative measures based on the Bible for embryonic stem cell research, cloning and euthanasia.

First of all, how does a group calling themselves the ‘Coalition of Americans for Research Ethics’ adopt a website entitled ‘stemcellresearch.org’? That aside, I am beginning to wonder if as a country we should be separating science and religion in the same way we seek to separate government and religion. I can respect that a person such as Dr. Prentice feels strongly about Christianity and how it impacts his daily life and I realize that for him there can be no separation between his work and his religion. But at the same time, I believe this makes him entirely unqualified to advise policymakers on issues of science. I think even Dr. Prentice would agree that simply having a Ph.D does not make your word gospel.

Finally, I have to say the editorial in Science is well written and well researched. As a scientist I’m pleased to see other scientists responding to Dr. Prentice with discourse and rebuttal, rather than dismissal. It is only through questioning and defending our work that we achieve validity. Read this if you have a chance:

http://www.dailyutahchronicle.com/media/storage/paper244/news/2002/02/28/Opinion/A.Separation.Of.Church.And.science-193464.shtml?norewrite200607150004&sourcedomain=www.dailyutahchronicle.com

Wednesday, July 12, 2006

Who has heard of the ORI?

So naturally the book had me wondering, does such an organization exist? And what is its history, its purpose?

Well it turns out it does, check out http://ori.dhhs.gov/

It seems the ORI has a detailed plan for dealing with allegations of scientific misconduct. There are clear guidelines to follow, and the office seems to also offer support to institutions dealing with such allegations. The website points out that “responding to an allegation of research misconduct tends to be a unique rather than a routine event at most institutions”.

But how many cases does this office actually see yearly? How is it that after four years of doing research, reading about the NIH, being involved in my advisor’s NIH grants and submitting two NRSA grants of my own, this is the first I have heard of this organization?

According to the document “New Institutional Research Misconduct Activity: 1992-2001”:

“Most allegations made are not substantiated. Two hundred and forty-eight institutions opened 703 cases to process 883 allegations that resulted in 110 research misconduct findings by 76 institutions. Falsification was the most frequent allegations received; plagiarism the least frequent. Seventy-two percent of the 76 institutions that made research misconduct findings made only one. No institution made more than four.”

That means of 883 allegations only 12.5% were found to be actual research misconduct. I wonder how much this has to do with the Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics paper I mentioned in the June 27th post. Are scientists distrustful of each other?

Sunday, July 09, 2006

A scandal in norway

(http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/07/01/AR2006070100165.html)

"The errors and gaps that have been discovered are too many, too big, and too obvious that they can be blamed on coincidental errors, incompetence or such like," the commission's report said.

Further, the commission determined that Sudbo acted alone and that none of his coauthors were to blame. This strikes me as an incredible claim for scientific research, when you consider that the field is all about association. As we move out of our labs and into the greater community it is always what school are you from? Who did you train under? Who do you collaborate with? And scientists take great pains to surround themselves with credible, established researchers. We read drafts of papers, we look at data together, we edit, and we conference. I’m surprised that it would be possible to absolve coauthors and I have to wonder if those coauthors involved are truly absolved in the eyes of the scientific community.

Wednesday, July 05, 2006

Terry Wallis Wakes Up

Appearing today in Nature is a list of five blogs written by scientists that have made the technorati list of top 3500 blogs-

So congrats to the big five listed here: http://www.nature.com/news/2006/060703/full/442009a.html this is no small feat in the web universe.

Moving on- today’s post is regarding a piece that appeared in the Journal of Clinical Investigation this week (http://www.jci.org/cgi/content/full/116/7/1823) about a man, named Terry Wallis, who emerged from a minimally conscious state 19 years after a traumatic brain injury caused by a car accident. Doctors documented recovery of verbal skills, and further, they used magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging to detect changes in white matter pathology. In comparing the results of Wallis’s scan to that of a patient that did not improve, they speculated that axonal growth was responsible for his recovery.

Before we begin dredging up memories of Terry Schiavo and right to life discussions, it should be remembered that there is a major difference between a minimally conscious state (MCS) and a vegetative state (VS). As stated in the abstract of the JCI paper;

“Patients in MCS will show more than the purely reflex or automatic behavior observed in VS survivors, but they will nevertheless be unable to communicate their thoughts and feelings. Recent preliminary evidence indicates that MCS patients demonstrate improvement over a longer period of time and attain better functional recovery as compared with VS patients.”

In the early stages following injury it is possible to move from VS to MCS, although very little is known about the major differences between patients who are able to make this move and those who are not. In addition, little is known about the difference between MCS patients whose status does not change, and patients such as Terry Wallis who after 19 years begin to speak again. According to the bbc (http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/3052433.stm) Wallis’s doctors speculate that time spent with his family on weekends away from his Nursing and

Tuesday, July 04, 2006

A bit of social research-

Appearing last week in Science (http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/312/5782/1967) is an article describing how mice display empathy towards other mice. Researchers used a writhing test to see if real time observation of pain in one mouse would affect the pain behaviors of another. They additionally tested these pairs when they were strangers, cagemates or siblings. Their results indicate that when mice are exposed to another mouse experiencing pain, their pain behaviors are also modulated. They further tested the nature of this social modulation by systematically blocking each sense; sight, sound, smell, touch, and they determined that the only way to block the increase was to block the mice from seeing each other.

Do mice experience empathy? Do they notice their counterparts experiencing pain and respond in kind? It must be somehow different from their concept of fear, because logic would dictate that a counterpart in pain may be experiencing something dangerous that must be avoided. Can mice tell the difference between pain and death?

The study reminded me of a recent communication in Nature (http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v441/n7092/full/441421a.html), which determined that lobsters are capable of identifying and avoiding other sick lobsters. This makes more sense to me; it is tied to an instinct for preservation.